A work related tragedy

A recent tour of the Sydney Trades Hall and its history caused some thinking on Health and Safety issues and how they have improved incredibly over the years. I recalled the various inscriptions upon monuments in the Cemetery and it is one disaster that came to mind.

BALMAIN COLLIERY DISASTER OF 1900

Coal was an essential component for 19th century industry. With seams in the Illawarra and Hunter areas it seemed logical that there would be coal under Sydney Harbour somewhere. If found this would be of great benefit to local industry and exporters. A Company, Sydney Harbour Collieries Ltd., was formed in England in 1896, acquired mining rights and started to explore.

A seam was found near Cremorne Point, but it was decided that this area was not suitable for the heavy industry involved with coal mining and it was decided to access this seam from the suburb of Balmain.

A site was selected at the corner of Birchgrove Road and Waters Street and work began in 1897 with the sinking of two shafts. 1897 was Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee year so the shafts were named 'Birthday' and 'Jubilee' in her honour. Each were over 5m in diameter and had to be dug over 900m to meet the coal seam.

Coal Mine site - Dictionary of Sydney with thanks

The company was impatient to see some return on their investment and the 60 miners employed worked 24 hours a day in 3 x 8-hour shifts. Miners were raised and lowered in a large iron bucket which could swing freely. Safety precautions and guide rails used elsewhere were not engaged in order to save time and money.

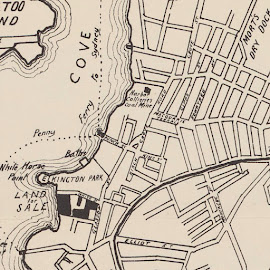

Balmain Colliery site and nearby surrounds - Dictionary of Sydney with thanks

By 1900 the seams had still not supplied coal.

On the 17th of March 1900 at the changing of the shift at 3pm, six men, the maximum load, were lowered down the 'Birthday' shaft to a depth of 540m. As was the usual practice the men stood with one leg in the bucket with the other dangling outside; one man carried the kerosene flare that provided light for the descent. The flare extinguished a few metres from the head of the mine, leaving the men unable to see the walls and keep the bucket from descending evenly. At about 350m, the bucket, which had been swinging quite randomly, struck a bunting (a projection from the wall) tipping it over from the base throwing five of the six men to fall the rest of the distance. William Watkins was left clinging on to the handle with his feet dangling and unable to regain his position back in the bucket when it stopped swinging. He received lacerations to his head and sustained a badly injured hand but was eventually lowered to safety.

Unfortunately, his colleagues fell to land at the feet of the horrified men working below who reported hearing a rushing sound. All five men did not survive the fall.

The inquest which was heard soon after could not decide what had caused the bucket to sway; it was suggested that one of the men may have had a "turn" and lost momentum, but this theory could not be determined eitherway.

The jury declared that the workers died from 'injuries accidentally received’ and recommended that in future every person employed to descend the sinking shaft at the colliery must be examined by a medical practitioner at least once every six months.

The Mining Act was amended to make guard rails in shafts compulsory and the Balmain Colliery miners, in recognition of the great depth that they worked, were allowed safety belts which attached to the hook holding the bucket handle.

The funeral was held on the 19 March immediately after the hearing of the inquest. The cortege left the Colliery at 3pm and proceeded through the streets of Balmain to St John's Church of England for the church service. The procession then took the journey to the Mortuary Station at Chippendale (Central Station south). It was led by 150 Colliery employees followed by 5 horse drawn hearses, many mourning coaches for family and Mine officials. A special train, provided by the Company, took mourners to Rookwood and a service at the graveside.

At a time when welfare payments were scarce, if any, the men's insurance company paid out £50 to each heir to pay for the funeral expenses. What other compensation was paid is unknown.

Coalmining continued and the 'Birthday' shaft finally reached the coal seam in November 1901 with the first coal load brought up in June 1902. The mine closed in the 1931 when its owners went into liquidation. Some mostly unsuccessful attempts to find gas followed, but eventually in the 1950s the 'Birthday' and 'Jubilee' shafts were filled in with fly ash from the nearby White Bay Power Station and concrete seals placed on the shaft heads. The site is now occupied by Hopetoun Quays, a development of more than a hundred townhouses.

The incident on 17th March 1900 claimed the lives of 5 men: Philip Jones (19), Theodore Travers (22), Alexander Robertson (35), Charles Munnings (28) and James Smith (35).

Burial site with monument for the five men who died at the Balmain Colliery on 17 March 1900 - photo author's own

They lay side by side in a large plot in the Old Anglican Ground at Rookwood near the Red Ornamental Rest House (or Elephant House as it is commonly known) under a large, impressive monument. A marble carving of the headworks of the mine with crane, rope and bucket, indicates they were miners and is engraved as follows: -

"Erected by the Officials & Employees of the Sydney Harbour Colliery. To the memory of the men who were accidentally killed at the mine."

Each name and age is recorded on separate marble plates, which are set into the base kerbs.

Monument detail - photo author's own

Why does it always seem that it takes a dreadful accident for reforms in Occupational Health and Safety legislation to be enforced?

If you have any comments, please leave them below or at the Group Facebook page which you can find under a search of

rookwoodcemeterydiscoveries

or simply send me an email at

lorainepunch@gmail.com

Another very informative post, thanks Loraine…

ReplyDeleteThank you and thank God for modern OH& S measures

Delete